Coming Out in Class: Challenges and Benefits of Active Learning in a Biology Classroom for LGBTQIA Students

Abstract

As we transition our undergraduate biology classrooms from traditional lectures to active learning, the dynamics among students become more important. These dynamics can be influenced by student social identities. One social identity that has been unexamined in the context of undergraduate biology is the spectrum of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA) identities. In this exploratory interview study, we probed the experiences and perceptions of seven students who identify as part of the LGBTQIA community. We found that students do not always experience the undergraduate biology classroom to be a welcoming or accepting place for their identities. In contrast to traditional lectures, active-learning classes increase the relevance of their LGBTQIA identities due to the increased interactions among students during group work. Finally, working with other students in active-learning classrooms can present challenges and opportunities for students considering their LGBTQIA identity. These findings indicate that these students’ LGBTQIA identities are affecting their experience in the classroom and that there may be specific instructional practices that can mitigate some of the possible obstacles. We hope that this work can stimulate discussions about how to broadly make our active-learning biology classes more inclusive of this specific population of students.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA1; see Table 1 for a set of definitions relevant to this paper) make up an estimated 3.6% of the overall U.S. population (Gates and Newport, 2015). As a group, LGBTQIA individuals have been thought to be historically underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), but few empirical studies have been done (Patridge et al. 2014; Cech, 2015). We also know very little about the undergraduate STEM experience for individuals who identify along the LGBTQIA spectrum, making it difficult to pinpoint why LGBTQIA individuals are at risk for leaving STEM. Institutions rarely collect this demographic information from students, and there are only a small number of studies that have explored this population in the context of STEM education (Cech and Waidzunas, 2011).

| Language and labels are important for this community, especially because of historical stigmas associated with particular labels. It is important for members of the LGBTQIA community to have choice over what term to use to describe their identities. Many of the terms below have multiple definitions. We chose to define each term in a way that most closely reflects the way in which it is used in this paper. We outline a set of definitions that could aid the reader in better understanding this social identity.a |

| Asexual: A term used to describe someone who does not experience emotional, physical, and/or sexual attraction |

| Being out: Not concealing one’s sexual identity or gender identity |

| Bisexual: A term used to describe someone who is emotionally, physically, and/or sexually attracted to both men and women |

| Cis-gender: A term used to describe someone whose gender identity and biological sex assigned at birth align (e.g., identifies as female and female-assigned at birth) |

| Coming out: Voluntarily making one’s sexual identity or gender identity known to others |

| Gay: A term used to describe individuals who are primarily emotionally, physically, and/or sexually attracted to members of the same gender. This can be used to describe both men and women. |

| Gender fluid: A gender identity that describes someone whose gender identification and presentation shifts over time |

| Gender dysphoria: A condition in which one feels discomfort or distress because one’s emotional and psychological gender identity is different from one’s biological sex assigned at birth |

| Gender normative: The assumption that individual gender identity aligns with societal expectations for what it means to be a girl/woman/female or boy/man/male |

| Genderqueer: A gender identity label often used by people who do not identify with the binary of man/woman; or as an umbrella term for many gender nonconforming or nonbinary identities. |

| Gray-sexual or gray-asexual: A term that describes someone who identifies with the area between asexuality and sexuality. Some may prefer this term, because they experience sexual attraction very rarely, only under specific circumstances, or of an intensity so low that it is ignorable |

| Heteronormativity: Norms and practices that assume binary alignment of biological sex, gender identity, and gender roles and establish heterosexuality as a fundamental and natural norm |

| Heterosexism: The assumption that all people are or should be heterosexual. Heterosexism excludes the needs, concerns, and life experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer people, while it gives advantages to heterosexual people. It is often a subtle form of oppression that reinforces realities of silence and invisibility. |

| Heterosexual: A term that describes someone who is emotionally, physically, and/or sexually attracted to members of the opposite gender |

| Homosexual: An outdated term that describes a sexual orientation in which a person feels physically and emotionally attracted to people of the same gender |

| Intersex: Describes someone whose combination of chromosomes, gonads, hormones, internal sex organs, and genitalia differs from the two expected patterns of male and female |

| Lesbian: A term used to describe women attracted emotionally, physically, or sexually to other women |

| Passing (gender identity): Occurs when one is recognized as the gender identity one identifies as (e.g., a trans-male being recognized by others as male) |

| Passing (sexual-orientation identity): Occurs when someone of a minority identity is assumed to be a member of a majority identity (e.g., someone who identifies as gay is assumed to be straight) |

| Pansexual: Describes someone whose emotional, physical, and/or sexual attraction is not limited by sex or gender identity |

| Queer: An umbrella term used to describe individuals who identify as nonstraight. Also used to describe people who have a nonnormative gender identity. It is important to note that some members of the community may find this term offensive, while others take pride in reclaiming it. |

| Straight privilege: A term used to describe societal privilege that benefits individuals who identify as (or are perceived to identify as) straight that is denied to members of the LGBTQIA community |

| Transgender: A term used to describe a person who lives as a member of a gender other than that expected based on anatomical sex designated at birth |

LGBTQIA identity is a unique social identity for a number of reasons. First, it is often an invisible identity, meaning that people may need to “come out” to let others know that they identify that way (de Monteflores and Schultz, 1978; Reynolds and Hanjorgiris, 2000; Quinn, 2006). We live in a heteronormative and gender-normative society in which sexual orientation is typically assumed straight until told otherwise, and gender is usually assumed to align with biological sex unless otherwise indicated (Chrobot-Mason et al., 2001; Kitzinger, 2005; Bilimoria and Stewart, 2009; Braun and Clarke, 2009). Second, awareness and saliency of LGBTQIA identity changes over time, and for some individuals, there is a degree of fluidity and rejection associated with their identities (Kinnish et al., 2005; Morgan, 2013). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity development often occurs between ages 12 and 25, but each LGBTQIA individual has a unique timeline for becoming aware of and internally accepting his/her/their identity (de Monteflores and Schultz, 1978; Rust, 1993; Calzo et al., 2011). Finally, LGBTQIA is a social identity that is still stigmatized to some degree and can be a source of tension, particularly for individuals and their families with certain beliefs or religious identities (Newman and Muzzonigro, 1993; D’Augelli et al., 1998; Etengoff and Daiute, 2014). As such, many members of the LGBTQIA community may feel as though they need to conceal their identities, at least in certain situations, and sometimes the decision to come out is associated with concern for losing straight privilege (Goffman, 1963; Chrobot-Mason et al., 2001; Quinn, 2006; Orlov and Allen, 2014).

Undergraduate classrooms are particularly relevant places to examine the experiences of LGBTQIA individuals, because many individuals begin exploring their LGBTQIA identities during college (Vaccaro, 2006). To our knowledge, there are no studies of the experience of LGBTQIA students specifically in undergraduate classrooms. The limited research on the experiences of LGBTQIA students in college more generally indicates that they have been subjected to overt homophobia, subtle discrimination, and feelings of isolation on some college campuses (Herek, 1993; Rhoads, 1994; Love, 1997, 1998; Rankin, 2003; McKinney, 2005). These experiences can negatively affect the mental health of LGBTQIA students; for example, lesbian and bisexual college women are more likely to experience mental health issues such as anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms, self-injury, and suicidal attempts than their straight counterparts (Kerr et al., 2013). Although much has changed recently as far as public opinion and campus climate regarding this social identity (Dugan and Yurman, 2011), including the national legalization of marriage equality in 2015 (Obergefell v. Hodges), there is still evidence that LGBTQIA individuals face discrimination and double standards compared with their straight counterparts (Human Rights Campaign, 2015; American Physical Society [APS], 2016; Mishel, 2016). For instance, LGBTQIA instructors perceive that they could lose their professional authority if they come out to students (Russ et al., 2002). A 2014 survey of workplace climate, including faculty members, found that 70% of participants said that talking about gender identity or sexual orientation in the workplace was “unprofessional” (Human Rights Campaign Foundation, 2014), and the term “heteroprofessionalism” has been coined to describe how gay men are discouraged from expressing an identity that is seen as outside normal (Mizzi, 2013). The 2016 LGBT Climate in Physics report concluded that isolation was a common theme for many LGBT physicists (APS, 2016). Even though coming out at work and working for an organization that was presumed to be more supportive of the LGBTQIA community was related to higher job satisfaction and lower job anxiety (Griffith and Hebl, 2002), there is still a prevalent view that it is irrelevant to share LGBTQIA identities in the workplace, especially the scientific workplace (Bilimoria and Stewart, 2009), and many scientists are not out to most of their colleagues (APS, 2016).

STEM disciplines are historically dominated by white, straight, cis-gender men (National Science Foundation/National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2015), and these disciplines in particular have been prone to a lack of tolerance and/or acceptance for the LGBTQIA community (Bilimoria and Stewart, 2009; Cech and Waidzunas, 2011; Cech, 2015; Patridge et al., 2014; APS, 2016). Unlike non-STEM disciplines, STEM disciplines are typically assumed to be objective and devoid of influence of social identities, which may be why STEM disciplines are generally less accepting of individuals sharing their LGBTQIA identities (Bilimoria and Stewart, 2009). LGBTQIA employees in STEM fields report more negative experiences due to their identities than LGBTQIA employees in non-STEM fields (Cech, 2015). Further, scientists who are out to their colleagues report pressure from their STEM colleagues to “tone down their ‘gayness’” (Bilimoria and Stewart, 2009, p. 90; APS, 2016). In the college context, LGBTQIA engineering students have to “navigate a chilly and heteronormative engineering climate by passing as heterosexual,” and issues of sexual orientation are usually considered irrelevant or inappropriate in the engineering environment (Cech and Waidzunas, 2011). Thus, STEM classrooms may be particularly challenging places for students who identify as LGBTQIA.

As we shift our STEM classrooms away from traditional lecturing toward active learning (Freeman et al., 2014), the classroom climate changes. In traditional lecture classes, students could come to class and invisibly listen to a lecture. In contrast, in active-learning classes, students are asked and often required to actively engage with other students and the instructor (Eddy et al., 2014; Eddy, Brownell, et al., 2015a). While active-learning approaches have been shown to decrease achievement gaps among students of different social identities (Eddy and Hogan, 2014), the interaction among students in active-learning classrooms can promote greater awareness of who other students are and may exacerbate feelings of isolation for students who have a minority social identity. Students who are in a minority status in the classroom may try to remain invisible or seek out opportunities to work with other students who they perceive to be similar. In a recent study based in an introductory biology class, historically underrepresented racial minority students were shown to be more likely to prefer the role of listener in small-group work compared with white students, who preferred the role of leader (Eddy, Brownell, et al., 2015a). Another recent study in an active-learning introductory biology course showed that, over the duration of a semester, black students sought out other black students to work with, even if that meant moving outside the requested seating in the lecture hall (Freeman et al., in press, 2017). These studies support the idea that, in contrast to traditional lecturing, active learning changes the dynamics of the classroom so that who the instructors and students are has a larger impact on the student experience, particularly for students who are in the minority. Given the small percentage of LGBTQIA students and the likely lower perceived percentage of LGBTQIA students, since most students are not out to the whole classroom, we hypothesize that LGBTQIA students hold perceptions that they are in a minority status in most classrooms.

In this study, we set out to examine the experiences of LGBTQIA students in undergraduate biology classrooms, with specific interest in how active learning could influence that experience. In this paper, we use Tinto’s theory of college student departure (1975), which focuses on social integration in an active-learning classroom, as a lens to explore the unique experiences of LGBTQIA students. Tinto proposed that social integration, defined as student involvement in the social system of college (e.g., interactions with peers and faculty), is a key predictor of student persistence in college (Tinto, 1975, 1997). He proposed that participating in collaborative-learning groups in the classroom context, which was called active learning in the model by Braxton and colleagues (2000), enables students to develop a small community of supportive peers. Participating in active-learning classroom activities may help students develop peer relationships that help them to integrate into the larger college community and, ultimately, may lead to increased persistence in college.

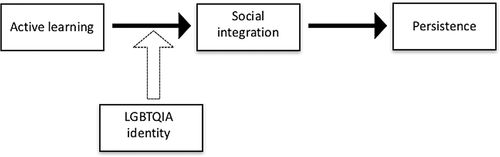

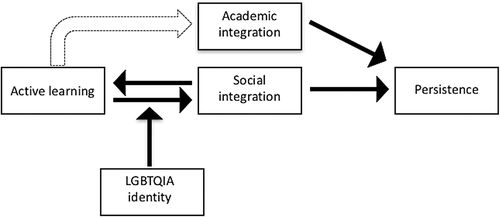

While Tinto recognized the potential for student social connections to emerge from collaborative-learning activities, he did not explore the direct impact of students’ social identities on the development of peer relationships stemming from these activities in the college classroom (Tinto, 1997). As we transition our classrooms to be student centered, with more opportunities for students to engage with instructors and with one another, we suspect that students’ social identities will become more apparent and important as students form and strengthen social connections within the classroom. However, we must be mindful that, while active learning may provide opportunities for social inclusion in the classroom, some students may feel more isolated if they perceive that their identities are not accepted or acknowledged. As such, in this study, we used an adapted Tinto’s theory of student departure that includes social identities as a key factor in the development of social integration through active learning (Figure 1). Using this lens, we explore the experiences of LGBTQIA individuals in undergraduate biology classrooms that adopt active-learning teaching strategies. We hypothesize that their identities will influence how active learning leads to social integration.

Figure 1. Hypothesized influence of social identity on an abridged model of Tinto’s theory of college student departure.

METHODS

Institutional and Classroom Context for Recruitment

We recruited students from one upper-level undergraduate biology course at a large public research-intensive institution in the U.S. Southwest. This course was cotaught by a male and a female instructor in an active-learning way that relied on student group work in nearly every class session. Students were asked to complete assignments outside of class based on the readings to help prepare for class. Class sessions of ∼180 students were held two times per week in a large lecture hall with traditional seating. Roughly 70% of the lectures were spent on student-centered activities, which almost always involved group work. Individual instructor approaches to active learning varied but often included clicker questions with peer discussion, students completing worksheets in groups, and students comparing concept maps with one another. Students also met for one class session per week (called recitation) in a studio classroom for approximately 45–60 students with tables for six students each. Approximately 90% of the recitation sessions consisted of student-centered activities, which always were structured around group work. In both the lecture and the recitation, students were usually able to choose whom they sat next to and worked with, although the instructional team typically prompted students who were sitting or working alone to join a group.

Recruitment

An instructor of the course sent out an email to the whole class that invited students who identify as a member of the LGBTQIA community to participate in an interview about LGBTQIA student experiences in undergraduate biology courses in hopes of creating a more inclusive biology community. Students were informed that they would receive a gift card in return for participating.

Of the 181 students enrolled in the course, seven students responded with an interest to participate in the interviews. This 3.9% of the class aligns with the national estimate of 3.6% of the population identifying as part of the LGBTQIA community (Gates and Newport, 2015), making it likely that we recruited most students from this class who identify as LGBTQIA. While seven students is a small number, it is important to keep in mind that most studies on LGBTQIA students have small sample sizes, given how difficult it can be to access this population. One of the strengths of our recruitment is that we had a diversity of LGBTQIA identities represented in our sample, including transgender and genderqueer students who are rarely studied. Further, because we sampled from a single class that used active learning and group work extensively, we were able to document both shared and unique experiences of LGBTQIA individuals in response to the same active-learning environment. Finally, given the general paucity of information on the experience of LGBTQIA students in undergraduate biology classes, this exploratory qualitative study is an important first step in documenting their experiences, and the opinions of these students are sufficient to begin to explore these questions.

Data Collection

We conducted two sets of semistructured interviews, all of which were conducted by one interviewer (K.M.C.). Each interview was audio-recorded, transcribed, and then coded for themes and subthemes by two reviewers (K.M.C. and S.E.B.) using a combination of content analysis and grounded theory (Glaser et al., 1968). The semistructured interview format allowed the interviewer to explore interesting topics that came up in conversation with different students. Therefore, a topic explored in depth in an interview with one student may not come up in an interview with a different student. For this reason, the topics that make up a subtheme were not necessarily explored with each student. The three major themes presented in the Results section were supported by data from interviews with all seven students unless otherwise noted. Student quotes were minimally edited for clarity and member checked (Patton, 1990). Data were anonymized, and pseudonyms have been given to the students.

The first set of interview questions was intended to explore the students’ LGBTQIA identities and how, if at all, their identities impacted their experiences and relationships in biology classes and the broader biology community (interview questions can be found in the Supplemental Material). We conducted this interview in the middle of the term. We suspected that students had not previously been asked about how their LGBTQIA identities might impact their experience in a classroom, so we decided to give students time to articulate their thoughts before the interview began. Immediately before the interview, we gave them a handout with specific priming questions (see the Supplemental Material). We gave them about 5 min to write down their thoughts, and students were told that they could use the piece of paper as a reference during the interview. Students expressed that having time to think through the questions just before the interview was helpful, because most had not been asked to discuss their identities in the context of the biology community. Some students referenced the handout when answering interview questions, and all students elaborated on their responses in the interview itself. We used grounded theory to identify interesting themes that emerged from the initial interviews that we wanted to explore further. Differences in student experiences between traditional lecture and active-learning biology classes emerged from the data and informed a second set of interview questions.

In this second set of interviews, we used an adapted Tinto’s theory of college student departure (1975, 1997) as a lens to explore how, if at all, students’ LGBTQIA identities impacted their active-learning experiences and subsequent social ties to other students in the classroom. The second set of interviews was conducted with the intention of exploring participant experiences as LGBTQIA students in active-learning and traditional lecture biology courses. Questions were created to align with this theory (interview questions can be found in the Supplemental Material). The second set of interviews was conducted within a month after the active-learning course had ended to ensure that students felt they could talk freely about their experiences in the course without having to worry that it would impact their grade, but before they would forget details about their experiences.

This study was done in accordance with an approved IRB.

Qualitative Approach

We predicted that the ways in which LGBTQIA identities influence student experiences within an active-learning classroom would be unique to each student’s individual identity and the context of a particular setting. Therefore, we chose to explore our research questions using qualitative methodology, which studies people in the context of their situations (Taylor et al., 2015). Recruiting and interviewing students from the same active-learning biology class allowed us to minimize the variability of different settings and focus on how different students experience the same phenomena (Morse et al., 2002). This is particularly important, because there is not a single, agreed-upon definition of active learning (Freeman et al., 2014; Eddy et al., 2015b), and we were interested in exploring how students experience specific elements of an active-learning classroom (e.g., group work in this particular active-learning class). Limiting the population of this study to LGBTQIA students enrolled in the same upper-division biology course maximized our chances of saturating the data by identifying recurring themes (Morse et al., 2002). This exploratory interview study is a first step in identifying key themes that we suspect may be shared by LGBTQIA students in other active-learning classrooms, which would be of interest to explore in future studies.

RESULTS

LGBTQIA Participants

All of our interview participants had unique identities, backgrounds, and experiences. While we identified some interesting themes that emerged from the data, we cannot make any generalizations about whether these perceptions or experiences are true of the larger LGBTQIA population. We want to emphasize that these students are not intended to be representative members of that particular identity along the LGBTQIA spectrum. Individuals have different levels of saliency of the identity for themselves but also have different levels of being out to friends, family, and acquaintances. The identity itself, how important that identity is to the individual, and the degree to which the individual is out to others can all change over time. Thus, in this paper, we present the opinions and responses of seven students who identify in specific ways along the LGBTQIA spectrum at this particular point in time.

Further, even if two student responses represent a similar theme, it is highly likely that each student has a nuanced experience in the classroom as it relates not only to an LGBTQIA identity but also to other social identities (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status). To capture these personalized experiences, we often included quotes from different students throughout the paper to illustrate findings. These findings are meant to be exploratory and thought-provoking, but future work needs to be done on this understudied population to delve into the intersectionality of students’ other social identities.

Language is particularly important for members of the LGBTQIA community, including the label that individuals use to describe themselves. For example, a female who is interested in a same-gender partner may prefer the term “lesbian” or “gay” or “queer,” and it may be important for her sense of identity that her preferred label is used. As much as possible, we tried to describe participants’ LGBTQIA identities both in and outside the classroom using their own language. We summarize these data in Table 2.

| Student | Self-described LGBTQIA identity | Description, timeline, and importance of identity to student (using the students’ own words) |

|---|---|---|

| Sonja | Lesbian | Sonja identifies as a lesbian and prefers the pronouns “she/her.” She has known that she is a lesbian since she was young and feels that the identity is very important to her. She first came out in middle school and now considers herself to be very out. Some of her family and most of her friends know that she is out. She thinks that when people see her, some people think that she is a lesbian, but others do not. |

| Allan | Gay | Allan identifies as gay and prefers the pronouns “he/him.” He considers his gay identity an integral part of who he is. He first came out in high school and is now out to his family and most of his close friends. Allan thinks that he typically passes as straight. |

| Josephine | Gay | Josephine identifies as gay and prefers the pronouns “she/her.” Josephine does not feel that her gay identity is central to who she is, although she perceives that it changes the way she thinks. She first came out in high school to her family and a few friends and is now out to her close friends. She perceives that others recognize that she is gay. |

| Margaret | Bisexual | Margaret identifies as bisexual and strongly identifies as female. She prefers the pronouns “she/her.” Margaret’s bisexual identity is important to her. She first knew that she was bisexual early in high school and came out soon after she realized her identity. She is out to her family and friends, but because of her specific identity (bisexual), she feels like an outsider in the LGBTQIA community. She perceives that she passes as straight. |

| Alex | Transgender | Alex identifies as transgender (female to male) and prefers the pronouns “he/him.” He has transitioned very recently, and his physical appearance/voice changed significantly over this term. He first started identifying as lesbian as a sophomore in high school before he learned more about the transgender community and started to identify as transgender. He explains that he has always kind of known that being transgender is his identity, but only within the past year and a half did he begin to identify as transgender. The identity is very important to him and he is 100% out. |

| Mar | Queer | Mar describes their primary identity as queer. They identify as trans-masculine, but also gender fluid and prefer the pronouns “they, them, their.” Mar describes feeling lost with who they were before discovering their identity within the past year. This identity is pretty important to them and has allowed them to establish important friendships. In the middle of the term, just before the first interview, Mar changed their name from “Kelcie” to “Mar” and felt as though they were coming out more. |

| Florence | Asexual | Florence identifies as asexual and prefers the pronouns “she/her.” Being asexual is really important to Florence, especially because she feels that most people do not know of or understand the identity. She has felt asexual her whole life, but she discovered the word to describe her identity about a year ago. She also uses the term gray-sexual to describe her sexuality, because she is not 100% asexual. At the time of the first interview, she was only out to five people; however, at the time of the second interview, she described being out to more people, including her family. |

Throughout the paper, we refer to these students as members of the LGBTQIA community. Although there are differences in the experience of individuals of a specific identity (e.g., gay vs. bisexual vs. asexual) that we lose by aggregating them into one group, there is some evidence that the experiences among gay, lesbian, and bisexual students are more similar than they are different in college environments (Dugan and Yurman, 2011). However, gender identity is fundamentally different from sexual identity, so it is likely that transgender students have distinct experiences, and there are limited data on how the experiences of transgender students compare with those of gay students. What is similar among all of these students is that they are managing their identities in a classroom culture that is currently heteronormative and gender normative and historically homophobic and heterosexist (Reynolds and Hanjorgiris, 2000).

Theme 1: LGBTQIA Students Do Not Perceive Overt Discrimination, but They Do Not Perceive the Biology Classroom Community Broadly as a Welcoming or Accepting Space for Their Identities

We probed broadly about whether students who identified along the LGBTQIA spectrum felt as though they were comfortable in undergraduate biology classrooms. Overall, we found that LGBTQIA students do not perceive the biology classroom to be accepting of their identities. We present several subthemes that emerged below.

LGBTQIA Students Feel That It Is No Longer Socially Acceptable to Be Overtly Homophobic, However, Students Still Experience Subtle Forms of Homophobia in the Biology Classroom

All participants stated that they felt as though it was not socially acceptable to be openly homophobic, although some of them mentioned that it was still acceptable to be transphobic:

Josephine (gay): “It’s very unpopular to be homophobic. Like, that does not fly.”

Margaret (bisexual): “I’ve talked to people who are, like, ‘I’m not homophobic, like, it’s cool if you’re gay, straight, or bisexual, but why do people have to change their sex? That’s what you were born as, that’s who you are.’”

The two students who identified as trans-masculine/queer and transgender indicated a higher level of concern than the other students for overt discrimination in the classroom setting. This may be due to having a more visible identity and/or it may be due to less general acceptance of transgender people in society (Lombardi et al., 2002; Lombardi, 2009):

Alex (trans): “I thought about telling my group mate about being trans but this is when Caitlyn Jenner2 started getting big, and he was just, like, ‘I don’t understand [transgender people], it doesn’t make sense to me.’ And I was, like, ‘Ehhh, all right. I don’t want to put that out there; I just want to finish the semester.’ There’s still a lot of close-minded people out there who don’t really accept the idea and they’re very transphobic.”

Mar (queer): “In society today, there’s a lot of violence about trans people, so it’s really scary to talk to people about being trans if you don’t know what their take on it is.”

Despite not perceiving overt homophobia, all but one of these LGBTQIA students indicated that, at some level, they perceived the undergraduate biology classroom to not always be a welcoming or accepting environment for their identities, although this was often perceived as being subtle and/or embedded in other beliefs:

Allan (gay): “I feel like a lot of the times I’ve heard homophobia from students hidden behind the fact that they’re not trying to seem homophobic. I think that’s the new thing now—it’s not acceptable to be homophobic—but people still are, so they do show their prejudice in different ways.”

Margaret (bisexual): “I feel like we’ve come a long way, where people can’t be saying something racist, but religion and people’s beliefs still mask homophobia.”

Sharing One’s LGBTQIA Identity with the Biology Community Is Perceived to Be Inappropriate

Several students discussed how sharing one’s LGBTQIA identity was inappropriate information to bring up in a science community, which echoes findings from other studies focused on STEM environments (Bilimoria and Stewart, 2009; Cech and Waidzunas, 2011). Margaret had a specific example of when someone told her that it was inappropriate to share her identity as someone who is bisexual. On a biology class discussion board, a student posted a comment that was negative toward transgender people, so she felt the need to come out about her own identity on the discussion board:

Margaret (bisexual): “So I mentioned that I was bisexual to merely sort of show that this matters to me, because I feel like I’m part of this community, and he was, like, ‘We don’t need to know your dirty secrets, we don’t need to know your personal life and I don’t go around flaunting who I have sex with,’ and it was really—it was really—that was the first time I was, like, ‘Really? I can’t even mention this?’ And I think it’s upsetting that the default is heterosexual and people just assume that’s what’s normal. He even said something like, I don’t think he used the word abnormal, but he said, like, atypical, like, ‘Don’t pretend- most people are this and you fall outside. We don’t need to know about people who fall outside of the norms.’”

In another example of how students did not perceive undergraduate biology classes to be accepting of their identities, Josephine reflected concern over whether she could share her LGBTQIA identity with an instructor. This internal struggle was reflected in her worry about whether coming out to an instructor would be considered unprofessional, even though she recognized this as a double standard that was not true for straight students:

Interviewer: “Talk to me about the potential benefits you see, if any, of being out to instructors in an active-learning classroom.”

Josephine (gay): “Coming out to instructors feels like mixing personal and professional. Yeah, it feels like it’s too easy to extend into the too personal category. I don’t think my professors want to care about my personal life, and I don’t think they should. I don’t know if I could share that. I don’t know. There’s something about that that’s like—there’s something about me that’s deeply uncomfortable with coming out to instructors.”

Interviewer: “If you were straight, do you think you would feel deeply uncomfortable for them knowing that about you?”

Josephine (gay): “No, and it’s hypocritical, and I recognize that it’s hypocritical. It’s very frustrating. See, like, I’m stuck. I don’t want to tell anybody that I’m gay, but I want to know things that I should know as far as professional consequences for being gay, and I just feel like those two things don’t work together.”

Josephine highlights this paradox between wanting to talk to people about how to navigate her identity in a professional setting and not feeling as though she can share her identity with faculty members. She feels as though this identity is “too personal” to share, even though this identity is an important component of who she is. Further, this student mentioned that she perceived “professional consequences” associated with being gay, indicating that she thinks being gay comes at a cost for her career in the broader biology community. She went on to elaborate on her worry of the potential backlash of being gay as a biology instructor:

Josephine (gay): “But then if you’re a junior faculty member, or if you’re, like, an instructor rather than tenure-track faculty, then there could be repercussions for coming out. I don’t know if people who work in supervisory roles or serve on committees decide on these things, but maybe you could offend somebody there. Or you could offend a student—which I think is a lot more likely. I wouldn’t want to be putting myself in the position where a student could complain about me any more than I’m sure the students already complain about me.”

Most of the students expressed some level of internal conflict about whether or not to express their identities in the biology classroom, although many of the students had difficulty describing their internal conflicts or explaining why those conflicts exist (McCarn and Fassinger, 1996). Interestingly, they illustrated concern for how other students would react to them coming out but could not seem to connect that concern back to why they were hesitant about coming out. Even though they all expressed that being a member of the LGBTQIA community is an important part of their identities, some worried about their identities not being taken seriously by others or that they could lose social and academic status or be negatively judged for identifying as LGBTQIA:

Allan (gay): “The risks I usually see are they view me as less of a person, or they view me as not even their equal, not intelligent, not their intellectual equal, and they don’t want to work on projects or anything with me by virtue of being gay.”

Margaret (bisexual): “I don’t feel like people who are bisexual are taken as seriously. And I feel like, in the professional world, people might see someone who is gay and be, like, ‘Well, they’re gay, you know they’re born that way or whatever, they can’t help it.’ But bisexual is seen almost like ‘You’re still playing around, you’re still messing around, figure it out.’ That’s how I feel. And bisexuals are seen as you’re really into sex. Like gay people can fall in love, and straight people can fall in love, but if you’re bisexual, you’re just having fun. I feel like that’s maybe the way people see it.”

Florence (asexual): “If I did bring up that I’m asexual, I don’t know if [other students] are going to be mean about it, or accept it, or be a little leery but ask questions and still be accepting.”

Mar (queer): “The risks of coming out to other students include being judged, being disliked, maybe discriminated against.”

Another student, Josephine, expressed concern that, if she came out, it would be perceived by others as making a big deal about her sexuality or her having a specific agenda related to her sexuality, even though she just thought of it as something personal:

Josephine (gay): “You never know what someone is going to think. You never know what beliefs other people have, and there are certain people who are just, like, ‘That’s wrong.’ I don’t want to be making a statement and I feel like it can be viewed that way, by coming out you’re making a statement, but I’m not trying to make a statement, I’m actively avoiding trying to make a statement.”

Students Report That They Would Feel More Comfortable in an Active-Learning Classroom Where They Knew the Instructor Identified as LGTBQIA, but They Worried about the Negative Impact of Coming Out on the Instructor or Other Students

We asked students whether they would feel more comfortable in an active-learning classroom where the instructor openly identified as a member of the LGBTQIA community. Six of the seven students said they would feel significantly more comfortable in a classroom where they knew that an instructor identified as LGBTQIA. All students mentioned that knowing an instructor was a member of the LGBTQIA community would positively affect them, because they would know they have something in common with the instructor. This seemed to be particularly important for the students who identified as queer and asexual, because they felt as though it was uncommon for them to encounter others with similar identities, especially instructors:

Florence (asexual): “I think I would feel more comfortable in a class if an instructor identified as asexual, because it would be nice to know that somebody feels the same way I do, which right now, would be very rare. I’ve never been able to talk to somebody who feels the same way I do. Like ever. So it would be nice to talk to somebody that feels the same way I do about people.”

Mar (queer): “I think I would feel more comfortable in a class where an instructor identified as queer, because I can relate to them on a different level. Not just on a student/teacher level. I think that if I think a professor might be queer, and I see them as a queer person, then I can also see them seeing me as a queer person. Not just visually seeing but seeing as that more underlying ‘I see you’ sense of the word.”

Despite the majority of students agreeing that they would feel more comfortable in a class if they knew the instructor identified as part of the LGBTQIA community, these LGBTQIA students still appeared to be apprehensive about instructors coming out to the entire class. They were concerned about how an instructor coming out would affect other students and how it might negatively impact the instructor. However, they recognized a double standard that straight professors talk about their spouses and children freely, and they never perceive a problem with straight professors talking about their families. This is evidence that these students perceive biology classrooms broadly to be unaccepting of LGBTQIA identities, even for the person with the most authority in the classroom:

Josephine (gay): “That’s their personal life. You know what I mean? I don’t feel like gay professors are obligated to say anything. I feel like a gay professor coming out to students could in a lot of situations just be kind of weird. Although when I think about it, I know a ton of my straight professors who are married or they have children.”

Allan (gay): “That’s a big move, especially in a lecture-style class with everybody who talks in biology, like, ‘Oh, don’t take them, they’re a homosexual or they’re gay or they’re lesbian,’ because I can see my peers doing that too.”

Margaret (bisexual): “You hear a lot of straight people talking about ‘my wife or my husband,’ and I think if a gay male faculty member said, ‘Oh, my boyfriend’ or something, and people would be, like ‘Whoa did he just say that?’ And it doesn’t happen. I’ve never had it happen before.”

However, Sonja, who identifies as lesbian, has a different perspective than the other students. She did not demonstrate any conscious worry about how welcoming the instructor or other students in the biology class would be toward her identity. She indicated that she did not like it when people questioned her identity or doubted that she was a lesbian and acknowledged that discussing LGBTQIA issues could make people upset, but that it did not impact how she felt about her own identity, nor did she feel it affected her experience in the classroom. At least outwardly in the interview, she did not exhibit signs of worry about what others thought of her identity. This is demonstrated in an example she gave of when she came out to another student in class:

Sonja (lesbian): “I don’t think I cared if they were going to be accepting or not to be honest. My group member was really nice about it, she even told me it’s fine, and I was, like, ‘Thank you, I appreciate that, but I honestly don’t think that you being OK with that or not is going to change who I am.’”

However, this is in contrast to the other students, whose statements indicated they broadly did not perceive the classroom to be a welcoming place for individuals, either for students or instructors, to express their LGBTQIA identities.

Theme 2: Active-Learning Classrooms Increase Interactions among Students as Well as between Students and Instructors, Increasing the Relevance of LGBTQIA Social Identities in the Classroom

All seven students indicated in some sense that they were more aware of their LGBTQIA identities in active-learning classrooms than traditional lecture classrooms. They perceived that, in traditional lecture classrooms, students do not need to interact with other students and instructors, so individual students’ social identities are less relevant. Several of the students indicated that they could be invisible in traditional lecture classrooms. However, in active-learning classrooms, students are requested, if not required, to work with other students, which seems to heighten students’ awareness of their own identities:

Allan (gay): “In a lecture there’s not as much time to talk about personal stuff. You’re mostly sitting there taking notes. That’s all we’re expected to do in a traditional learning class, so it doesn’t matter if I know their sexual orientation or political orientation or anything like that.”

Josephine (gay): “I’d sit by whoever in a traditional lecture, I don’t care. I don’t feel the need to be out in a traditional learning classroom. I don’t think there’s a lot of benefit there. Like, in a traditional lecture in biochemistry, I was totally comfortable going there, nobody knew who I was, nobody knew the first thing about me, and that was fine. Totally comfortable. But in an active-learning classroom, you have to interact with somebody. There’s not the same safety net of just kind of withdrawing.”

Florence (asexual): “Yeah, I usually won’t focus as much on how I choose my seat in a traditional lecture, because I know I’m not going to talk to that person ever, even though they’re sitting right next to me.”

Sonja (lesbian): “In an active-learning class, talking to each other is encouraged as opposed to a traditional lecture, you could just sit and not talk to the person next to you. It’s important, because if you’re doing active learning and you need to work with the people around you, you need to be comfortable with them or else you’re not going to contribute. You need, I guess, a comfortable environment to do so.”

Mar (queer): “In a traditional lecture class, coming out to other students is a choice that I wouldn’t feel pressured at all to make. I think, in an active-learning classroom, I might feel a little bit of pressure—if I felt like it would make my communication with someone better in an active-learning classroom—then there might be a bit of pressure to come out. In the traditional learning classroom, if there was pressure to come out, it would be only based on my relationship with that person versus the environment of the classroom in an active-learning classroom.”

Alex (trans): “In a traditional lecture class, I normally just pick a seat not close to people and mind my business. I don’t think about being transgender, because it’s a ‘get in, get out’ kind of thing. I mean sit and pay attention for as long as you can. When I sit down in a traditional class, I just kind of sit there and pull out my notebook and kind of do my own thing, I don’t really talk to the other people around me. I don’t just look at them and go, ‘Hey I’m Alex and I’m transgender.’ So I would only probably come out to the people in the active-learning one. In this active-learning class, first day, I just said to my group, ‘Hi I’m Alex, I’m transgender, please call me “he” even though I look like a “she.”’”

Sonja indicated that this active-learning class was the first college class in which she came out to the people around her. Although she had difficulty articulating why she came out to the people who sat next to her, she indicated that it had something to do with the interaction among students in an active-learning class:

Sonja (lesbian): “This is the first class that I have come out in, like, to the people around me. I don’t know why. I don’t know why, I can’t answer that. Maybe it’s just the fact that I talk to them. It’s only the people around me that know. In other classes, I don’t think it’s necessarily that I feel closeted, because if they were to ask me, I’d be, like, ‘Yeah.’ But the need for me to express my identity hasn’t been needed [in a traditional lecture class].”

Increased Interaction with Other Students in an Active-Learning Classroom Increases the Opportunity for Students to Be Identified Due to Their LGBTQIA Identities

Owing to the increased number of interactions among students in active learning, these students have to juggle learning biology content and deciding whether or not to either come out or to assert their LGBTQIA identities. Discussions about biology content in small groups often extend to more personal discussions in active-learning classrooms, which may lead to questions that put LGBTQIA students in the tenuous position of being forced to come out about their sexual orientation, change the topic, or lie:

Allan (gay): “Almost 90% of the time we discuss the biology problem and move onto something personal like ‘Where did you go to high school? What’s your major?’ And I always actively think that’s going to build into the questions that I don’t want to talk about.”

Josephine (gay): “So, basically, in these active-learning classrooms, socialization is normal, it’s so integrated with the way the learning is done. You have a lot more of the social interactions and in any particular interaction—and you have a lot more casual interactions. Like, in traditional classes, some people go with their friends and stuff, but a lot of people just show up and sit there. But before and after an active-learning class, I feel like a lot more people talk with people around them, and I feel like that is because you form closer connections, because you talk, because you’re required to. And then there can be these moments where you are basically confronted with a statement or a question that either is implying or questioning some sort of sexuality or gender construct that maybe doesn’t apply to you or you disagree with. And then you have to make a decision like ‘What am I going to say?’”

The students who believed that others perceive them as straight expressed that there is often an assumption that all students are straight, which means they have to come out in order to have their identities expressed. LGBTQIA students have to make the decision to share this information with people in a class, and sometimes there is not a good opportunity to talk about it, even if they want to share it:

Margaret (bisexual): “Being bisexual in a way that people look at me and they have no idea, they’re not going to jump to any conclusions. But then, I don’t know, it’s just awkward to be, like, ‘Oh by the way, I’m bisexual.’”

Allan (gay): “I feel like, as a white male, I’m very straight passing in general, and I don’t sound gay either. So I feel like I blend in more, because it’s not directly out there, and I don’t feel like people would be judging me, because to them, I’m straight. Coming out for me is active, like I have to say it.”

Florence, who identifies as asexual, indicated that she felt more of a need for her to be out to active-learning classrooms than traditional lectures, because of the higher degree of interaction with other students:

Interviewer: “Talk to me about any potential benefits you see, if any, of being out to other students in an active-learning classroom.”

Florence (asexual): “People won’t randomly flirt with me and they won’t think if they’re nice to me, then something is going to happen. That’s happened way too many times. ‘I’m going to be nice to you, you should do something with me’ and I’m, like, ‘That’s weird,’ because I think of niceness as niceness, but apparently niceness is flirting. Usually, if they do the flirting and the hinting, and I’ll casually be, like, ‘Hey, I don’t really like people,’ and they’ll be, like, ‘Oh,’ and I’ll be, like, ‘Yeah, let’s go back to this work now.’”

Interviewer: “Do you think those benefits are different for you in a traditional lecture?”

Florence (asexual): “I feel like in a traditional lecture they just probably wouldn’t care. Usually I don’t talk to anybody.”

Interviewer: “So why do you think there are more opportunities for that in an active-learning classroom?”

Florence (asexual): “Because I think you get to know people better, and you talk to them more. Yeah, that’s it. You get to know them more.”

Allan, who identifies as gay, indicated that, for him, the advantage of being out in an active-learning class is that it could enhance the quality of the active-learning exercise, so he felt some motivation to come out in order to have a better academic experience:

Allan (gay): “The only benefit I can think of being out is working with [other students] regularly, it builds stronger friendships, it makes me feel closer to people, being out does make me feel closer to people. I feel like that leads to me having stronger debates or having more in-depth conversations past ‘I think A is the answer and I think A is the answer too,’ in the classroom. I think friendships are important in the classroom to facilitate active learning. In a traditional lecture course, you don’t necessarily have to be friends with the people that you sit around, and I feel like, in active learning, it helps improve the experience 100 times if you’re friends with the people around you.”

Increased Interaction with Other Students and Instructors in an Active-Learning Classroom Increases the Opportunity for Transgender or Queer Students to Be Misidentified

Students who wanted to pass as their preferred gender felt as though there was greater pressure in active-learning classrooms to come out, because there were more opportunities for misidentification:

Alex (trans): “I felt that it was very necessary for me to come out at the beginning of the semester, because there was a certain way that I wanted to be perceived, and I didn’t want to give people the opportunity to think otherwise.”

However, Alex indicated that, during group work in both active-learning lectures and recitation sessions, his group members consistently used incorrect pronouns, misgendering him, and he had to consciously decide whether to correct them and, further, reflect on why he had not been able to change his voice or physical appearance enough to pass as male:

Alex (trans): “I hate correcting people personally. So, like, if they say ‘she,’ I won’t really say anything, because I feel like it’s rude. I don’t like calling people out and potentially making them feel bad, even though I feel kind of dumb, like they still see me in a certain way, and that’s how they call me out, kind of, but I don’t want to try to fix it, so I just feel silly that they still see me that way.”

Although misidentification of a student’s identity can happen in either a traditional lecture class or an active-learning class, there is often also increased interaction between the instructor and students in an active-learning classroom. While at times this may provide students with additional opportunities to explain their identities to an instructor, it also increases the possibility of accidental misidentification. Specifically, Alex had a problem with instructors who misidentified him when they called on students in whole-class discussions. For example, Alex had an instructor who repeatedly would use the wrong pronouns but then would catch the mistake and correct it in front of the whole class. Not only did this bring attention to the student’s identity, but it made the student feel uncomfortable about being misidentified in front of the class:

Alex (trans): “It’s awkward. I don’t know if embarrassing is the right word, but it’s just kind of weird to be called both genders at the same time, like, ‘Oh, yeah, she, I mean, oh wait, he,’ and in my head, I was, like, ‘Ahhhhh, so frustrating!’ After class, the instructor would be, like, ‘I’m so sorry about this by the way,’ and I like, ‘Oh, it’s OK.’ I think, being transgender, you have to be open-minded about the people learning about transgender.”

While this student was trying to be patient with the instructor and saw this as an opportunity to help teach people about being transgender, the instructor misgendering him caused this student to become more aware of his transitioning status during class. Alex explained that, in traditional lecture classes, he did not usually participate in whole-class discussions, but because he knew the students and instructors in active-learning classes, he was more likely to speak out in class discussions. However, he also indicated that, at the same time, he was self-conscious of participating in front of the whole class, because he was concerned about how others would perceive him with respect to his gender:

Alex (trans): “Sometimes, because through the whole transition, your voice changing, it’s gotten a little bit deeper, so I wonder if the person is going to assume that I’m a dude or people are going to be, like, ‘Hey, look at that chick over there.’ The constant thing that I think about is how people are perceiving me. So when I talk in front of class— I’m talking out in front of the whole class, and all those people are seeing me, because I’m talking—and I’m wondering if they’re perceiving me the way that I want to or they’re seeing me as female.”

Student Concern Regarding Gender Identity May Increase Cognitive Load in Active-Learning Classrooms

Alex’s concern for how other students may perceive him also implies that he is spending class time thinking about his gender identity, increasing his cognitive load (Quinn, 2006). The effort required in maintaining an identity at the same time as learning biology means that these students are having to juggle multiple thoughts in their working memory (Sweller, 1988). Students who do not worry about how students perceive their gender do not have to occupy mental capacity in navigating these issues and instead can focus more on the academic content. Moreover, this misidentification and heightened cognitive load is less likely to happen in a class in which there are fewer interactions between the instructor and students, as well as among students. For example, Mar explains that, in active-learning courses with significant student discussion, they are especially aware of how other students perceive them, which prevents them from focusing on the material in class:

Mar (queer): “Even though I present in a way that makes me feel comfortable, my social anxiety unfortunately makes me take into account how other people see me. In discussion-based courses, I think it’s rougher for my emotional state when I feel like I need to talk to people, but I feel uncomfortable doing that, because I don’t know what their perception of me is, which is something I put a lot of value in. I worry ‘Do they like me? Do they think that I’m stupid? Am I trying too hard to let them know that I’m queer? Is that something that they’re going to think is ridiculous? Are they one of those people that wants to know?’ and ‘Do I want those people to know?’ It’s just so much pressure on talking to people and I think it takes away from what I get from a course if I’m focused on people’s perception of me versus what I’m actually supposed to be focusing on in the class. In classes that aren’t so discussion based, it’s easier for me to focus on the material.”

Active-learning classrooms are typically regarded to have more frequent assignments than traditional lecture classrooms. Whereas a traditional classroom may only have exams, most active-learning classrooms have weekly, if not daily, assignments. Often, students have to complete assignments outside class to demonstrate that they did the required reading. Additionally, some active-learning classrooms, including the one that we recruited from, frequently use worksheets in the class on which students put their names. For students who are in the early stages of transitioning and/or have not yet legally changed their name, this means that, almost on a daily basis, they have to use a name they do not identify with in order to use email and course-management sites (e.g., Blackboard) and to complete assignments. Consequently, these students are not fully able to express their gender identities in the classroom when they are required to write their legal name:

Alex (trans): “I had to write my full legal name on my homework, because I was terrified that it wasn’t going to get entered, because the instructors would put my preferred male name in and be, like, ‘That name doesn’t exist in this class.’”

Mar, who identities as queer, transitioned names during that semester, so they began the class as “Kelcie” and then halfway through the term, they identified as “Mar.” This student indicated that, at the end of the term, they felt no connection at all with their former name. The instructors were aware of this student’s transition, so they informed the student that they could use the preferred name on assignments. This seemed to have a positive impact on the student. Mar stated that if they had been required to use the old name, then that could have been a reason not to come to class. Mar’s comment highlights this internal conflict that LGBTQIA students may experience between needing to follow the rules of school to be successful in the course and being comfortable with their identities, which for this student was dependent on using a name that is representative of their identity:

Mar (queer): “I wrote my name a lot more in an active-learning class, because we had all of those worksheets. I used my legal name on exams, because I didn’t want my grade to get screwed up, but the instructors had told me I could use my new name on the homework and the worksheet and stuff, and I started doing that. That made me feel pretty good. I don’t even associate with that old name, and that happened pretty quickly after I changed it, so it was weird to be using that old name.”

Interviewer: “Thinking about going through a name change in an active-learning class and if you had to write your old name all the time, how would that impact you?”

Mar (queer): “That would definitely impact how comfortable I felt in a classroom, and I don’t know if it would impact me majorly as far as if I were to go to class or decide to not go to class, but I think it would play into that.”

Active-Learning Classrooms May Provide Additional Opportunities for Students to Come Out and Find Similar Others

Although active learning presents a number of challenges for LGBTQIA students in terms of a greater emphasis on their identities, there are also some positive opportunities associated with active learning compared with traditional lectures. For example, active-learning classrooms may provide LGBTQIA students with a larger number of opportunities to come out and find people who share similar identities. In the class from which these students were recruited, all of the students were asked at the beginning of the term to write their preferred names on name tents. They were asked to bring the name tents and display them during each class. Alex decided to write his preferred pronouns on the name tent to help people around him know which pronouns he preferred. This was how the instructors of the course became aware of him being transgender, so they started using his preferred pronouns. It eliminated the need for a student-initiated conversation about gender with his instructors:

Alex (trans): “I had the idea of writing ‘he, him, his’ on my name tent at the beginning of the semester so, hopefully, people would use it. There were a lot of people who still kind of didn’t, but there are people, like the instructors, who were able to pick up on it.”

The increased interaction with other students in the active-learning class also gave LGBTQIA students the opportunity to teach them more about their identities and for LGBTQIA students to meet other LGBTQIA students:

Alex (trans): “Coming out to other students in an active-learning classroom gives [other students] the opportunity to learn more about how I identify. I wouldn’t have met two other LGBTQIA people if I wouldn’t have introduced myself the way that I did and then they wouldn’t have someone they could relate to also. I feel like since I was able to come out and introduce myself that way, another student was able to make a connection, and I was able to give him resources, like, there’s a group that meets every other week downtown and trans guys and trans women get to meet up and talk about stuff like that. In an active-learning classroom, I feel like I get to reach out to other people who don’t have that opportunity to be open about it.”

Margaret (bisexual): “Maybe someone could benefit from sitting with somebody who is gay because they could talk to this gay person and the gay person could be really, really cool and blow their perception of gay people.”

In fact, it has been shown that individuals who have more contact with LGBTQIA individuals in college tend to have more positive attitudes in general toward members of the LGBTQIA community (Liang and Alimo, 2005). Thus, active-learning classrooms in which students feel comfortable enough to come out could have positive implications for the LGBTQIA community that extend beyond the classroom.

Theme 3: Group Work in Active-Learning Classrooms Presents Situations for LGBTQIA Students to Be Uncomfortable

How comfortable students feel is influenced by their own social identities and the social identities of others around them, particularly in their small groups (Eddy, Brownell, et al., 2015a). We found that nearly all of our students were mindful about who they sat next to, because they wanted to work with someone who would be accepting of their identities.

LGBTQIA Students Tend to Be Mindful about Who They Collaborate with during Group Work, Because They Prefer to Work with Others Who Are Accepting of Their Identities

Students indicated that, at times, they used past experiences with students who have specific social identities as a metric for how accepting members of those social identities would be toward them now. In short, they stereotyped people based on some characteristic that they associated with not being accepting of their LGBTQIA identities. Students admitted that they felt somewhat uncomfortable profiling people’s acceptance based on their membership in another social identity, but that it was a way to try to quickly find people who would be more likely to accept their identities. Specifically, some students mentioned that they avoided anyone who looked as though they were members of a fraternity or sorority, because they perceived that those students would be less accepting of their LGBTQIA identities. They often used membership in a fraternity or sorority as a way to categorize individuals who were hypermasculine or hyperfeminine, characteristics of individuals who have been shown to harbor more intolerance for LGBTQIA individuals (Caballero, 2013; Worthen, 2014):

Allan (gay): “In a quick cost–benefit analysis, I usually avoid people who are wearing fraternity clothing. I have existing prejudices against straight guys, mostly from high school, and I guess I just carried it over. I just shy away from them in the first point, because where I do see prejudice towards me, it usually comes from that specific group of people. So I shy away from them, because I’m more comfortable working with females or other gay students. And if I can find another gay student, that’s fantastic, but that’s hard, so it tends to be female students.”

Margaret (bisexual): “I mean if I see really super-prissy sorority girl—I think a girl like that would be, like, ‘Oh my god, she’s trying to hit on me’—I feel like maybe she would freak out or something.”

Students also said that they used political or religious cues as indicators for whether someone would be accepting of their LGBTQIA identities. Again, they stated that they knew that many religious people and conservative people were accepting of their identities, but they felt that, given the costs associated with not being accepted for their LGBTQIA identities, they wanted to play it safe. As a result, they usually tried to avoid students they knew were religious or politically conservative based on their past experiences with those students. They also tended to not sit next to students who wore visible crosses or religious shirts. These students’ assumptions that individuals who are religious or politically conservative are less likely to be accepting of LGBTQIA individuals are supported by the literature (Nagoshi et al., 2008; Hooghe et al. 2010; Holland et al., 2013):

Interviewer: “Do you wonder whether the person you’re working with would be accepting of your gay identity?”

Josephine (gay): “Yeah, sometimes. I wonder about these people who are very religious, because traditionally they do not accept, and that’s the main thing I can think of, or maybe if someone was wearing Donald Trump 2016,3 I would question.”

Allan (gay): “I look for crosses, but then again that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re super-religious, but I have the tricks. I look for maybe religious clothing, and I don’t try to judge religious clothing, whether it’s Christian or Muslim or anything, but I just try to avoid those people.”

Florence, who identifies as asexual, would try to avoid sitting next to anyone who seemed romantically interested in her:

Florence (asexual): “Actually, if someone is looking at me weird, I’m probably not going to sit next to them. And by weird I mean really looking at me, like up and down kind of thing, like I’m giving myself too much credit, but in a sexual way. I’m just, like, maybe not, that might be a bad idea, that might get weird. It DOES get weird, and then I have to tell them I don’t really like people, and they’re, like, ‘Really?’ and I’m, like, ‘Yeah, I really don’t like people.’”

Coming into the class and finding a seat is not simple for these LGBTQIA students. Their responses indicate the need to navigate social, political, and religious boundaries to find people who would be most accepting of their identities. All of the students were very careful to indicate that they knew people in all of these demographic groups who were accepting of their identities and that they did not mean to classify any demographic group as anti-LGBTQIA. However, due to a combination of their own personal experiences and broader societal influences, they perceived that these demographic groups displayed a higher degree of intolerance toward them, and they wanted to avoid this possible lack of acceptance for their LGBTQIA identities.

Contrary to the other students, Sonja expressed that she did not think about whether other students would be accepting of her identity when choosing a seat in class or interacting with her classmates:

Sonja (lesbian): “I think if I were to sit next to someone who was not accepting of my identity, I wouldn’t care.”

Assigned Groups and Changing Groups Present Additional Challenges for LGBTQIA Students

In active-learning classrooms, assigned groups and changing groups during the term presented challenges for many of these LGBTQIA students. They had to “test the waters” with new group members to get a sense for their acceptance and, again, sometimes used religious and political identities as proxies for being accepting of LGBTQIA students. Students who felt as though they had a choice in whether to come out tried to establish whether a person would be accepting of their identities before making the decision to come out to that person:

Allan (gay): “I know some political stuff, I know religious questions, I probably probed them a little bit. So I can come out and be confident in how they’ll respond.”

Mar (queer): “There a lot of strong opinions on the Republican side about the queer community, and they’re not necessarily positive, it causes me to be a bit guarded if I know that someone is extremely Republican, and I know that I’m super-queer, I wonder, ‘What judgments are they making about me? Do they think that my identity is even valid.’ So communication would be hard for me.”

Florence (asexual): “So there’s a guy who sat next to me, he’s a Marine, very loud, very opinionated, he did not care about my bubble. I would definitely never tell him, because he would never understand. He’s very to the point, and when I suggested things to him, he really wouldn’t budge very much, and I just feel like he’d be one of those people who would say that asexuality doesn’t exist, ‘Why are you saying that? There must be something wrong with you or something.’”

Several students indicated that they particularly sought out other students whose physical appearance did not match gender norms, because they thought these people would be more accepting of their LGBTQIA identities:

Mar (queer): “For me, I end up navigating toward people with non–gender-conforming appearances. People who present feminine and have short hair. This person presents masculine but is wearing skinny jeans.”

Margaret (bisexual): “I mean, I think if I saw somebody who looked like they were definitely gay, I would probably rather sit next to them. Maybe I feel like gay people are more accepting of other people regardless, even if they didn’t think I was gay.”

However, it was not just as simple as finding other LGBTQIA students to sit with, because even within the LGBTQIA community, students may not necessarily understand or respect other LGBTQIA identities. Florence, who identifies as asexual, ended up working with Alex, who identifies as transgender, and it became apparent that both of them perceived that the other did not completely understand their experience, even though they both were members of the LGBTQIA community:

Florence (asexual): “It took Alex a really long time to come to terms with me being asexual. Because a lot of people don’t think it’s possible to be that way—they’re, like—you’re human, you’re supposed to want sex—there’s something wrong with you if you don’t. That’s how it is right now.”

Alex (trans): “Overall I think that the biggest struggle is when someone tries to identify trans, people just visually kind of type you and say whatever comes out first. Florence still calls me ‘she’ from time to time, and I’m, like, ‘Ugh, what is it? What?’ And she’s, like, ‘I don’t know, I just say it.’”

Assigned groups or changing groups during the term led to potential discomfort for most of the LGBTQIA students because of the potential for group members to not be accepting of their identities and the need to reestablish whether or not to come out. However, it seemed to be most uncomfortable for the queer and transgender students, who felt as though they must establish their identities, since pronouns would likely be used during group interactions. Because both of these students recently transitioned, they were often misidentified as female and had to correct group members for using the wrong pronoun or name. A new group meant having to spend time and energy to come out to the new group and to reestablish comfort in being able to correct other students’ misidentification of their gender. In fact, the queer and the trans student both felt very uncomfortable when they came to class late, because that meant that they usually had to sit in new groups:

Alex (trans): “Sometimes I’m not as comfortable right now with small groups, so I like sticking with the people that I know, just because they know how to address me. Not switching groups also kind of saved me the trouble of having to put myself in another situation where I would try to have to correct people or sit there and have people who didn’t know me keep misgendering me, and then I would be, like, ‘Argggg, I don’t really know you well enough to bring it up again.’ I don’t like to have to keep bringing it up. I didn’t really like sitting next to people I didn’t know, because I didn’t know how they would kind of take it, and even though I have my name tent out, I still get ‘she’ and ‘her-ed’ and I’m like, ‘Ehhh.’ I feel like sometimes, in recitation, when I switch to another group, because I’m always late, I start getting the ‘shes’ and the ‘hers’ and stuff a lot more often, and then it kind of makes me question, well what am I doing wrong that I’m not identifying to their standards of a ‘he.’”

Mar (queer): “Because I am working so hard on trying to present myself in a certain way and have people see me as a certain gender, I think that, in an active-learning classroom, not passing to someone, it makes me feel like crap, which happens a lot. And in an active-learning classroom, since you’re communicating with people a lot more than in a traditional setting, not passing to them, and knowing that you don’t pass, I think impacts you more than in a traditional classroom than where, if you don’t pass to someone, you don’t really have to recognize it, you can ignore it easier, because you don’t have to communicate with them again.”